Day Two - Katie Anderson's Japan Study Trip (Part 3)

We also visited a Japanese school called Tsuda Elementary School today. At first, I didn't understand why we visited an elementary school. However, this visit helped me understand the differences between how the concepts of "Lean" work in Japan and less so in the US. It is essential to understand how elementary schools work in Japan to understand this.

Japan has six grades, like the US, so students take at least six years to complete elementary school. The average student enters elementary school at the age of six and graduates at the age of twelve. Japanese elementary schools differ significantly from US elementary schools in several areas.

Moral Education

Kyushoku (給食) School Lunch

Cleaning School by Students

Moral Education

The Japanese Constitution prohibits the state from engaging in religious education or other religious activities. As a result, religion is not taught in Japanese schools. Schools in Japan instead teach "Moral Education Lessons." They aim to cultivate students' morality, honesty, judgment, engagement, and attitude. In this way, Japanese workers develop a consistent pattern of thinking. Whereas, for the most part, in the US, the responsibilities of a student's morality, honesty, and judgment are left to the family. One approach is not better, just that the Japanese education system is more likely to create these common societal traits.

Kyushoku

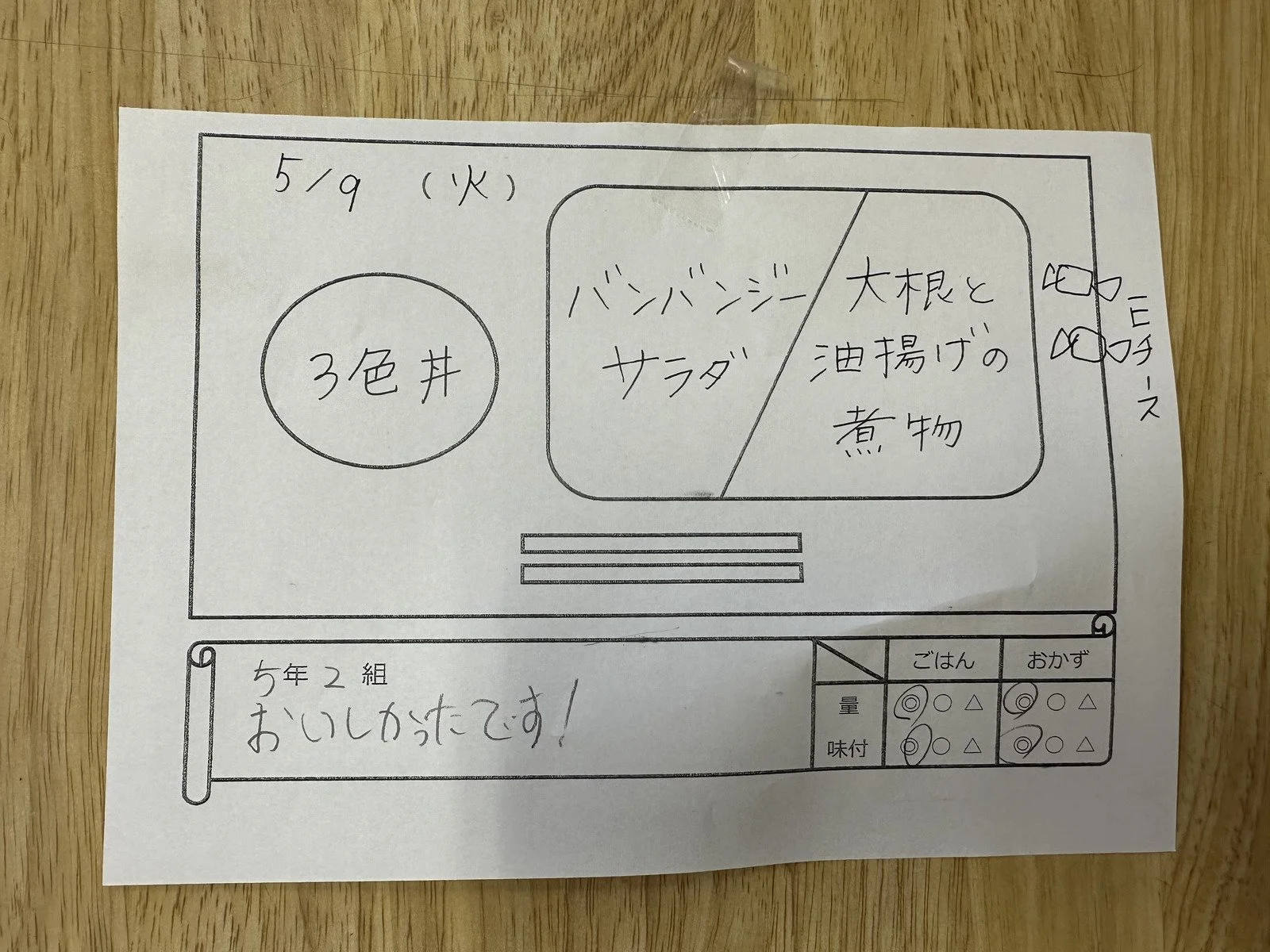

In Japan, Kyushoku (giving food) refers to school lunches served in elementary and junior high schools. It ensures that students eat a balanced diet regardless of their economic status. Students take turns serving teachers and classmates while wearing caps, smocks, and masks. They learn about teamwork, service, and responsibility at an early age. The students also create standard work forms as part of the lunch program. Students learn about hoshin (direction) and A3 (problem statement, analysis, proposed actions, and expected results) early.

The students design daily “Standard Work” forms for the lunch tray for each day’s lunch.

Seeing a petite 10-year-old in lunch lady/lunch man uniform was charming. Watching them serve not only the other students but they serve the teachers as well. They all had smiles on their faces. They were all having fun. The idea of service is not only taught as an inherent responsibility but also instills a sense of intrinsic accomplishment through servicing their peers. Aristotle's quote, "The Whole is Greater than the Sum of its Parts," pretty much sums up the Japanese student's experience.

Cleaning School by Students

The students themselves clean the school. They are responsible for classrooms, science labs, music rooms, hallways, and bathrooms. All of the students clean various parts of the school. In the classroom, basic cleaning supplies are stored in a common area. This week, we saw this in many factories where tools were in common areas, free to use. The workers and the students are trusted. They don't have to get permission or fill out a form to use a tool. The student's daily routine of cleaning the school helps them keep it clean without a school janitor. There are no janitors. Again, they do the cleaning with smiles while having fun. Service is taught as an inherent responsibility that instills a sense of intrinsic accomplishment.

In the 1986 movie Gung Ho, a Japanese company saves a failing US auto plant in the midnight hour. It was loosely based on General Motors' New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI) story. George Wendt's character Buster is given a broom and transferred to a janitor at one point. In a rage, he tells Hunt Stevenson, played by Michael Keaton, that he is quitting. Various stories have been told about Toyota employees sweeping the floor as part of the total quality control system with pride. Dr. Spear says that Toyota wanted all its employees to understand that the “pull” system was bigger than all its parts. Whether you worked on the brakes, and the steering wheel, or swept the floor, you were creating a quality car. Even though Gung Ho is a fictional story, this scene illustrates the stark contrast between American and Japanese workers.

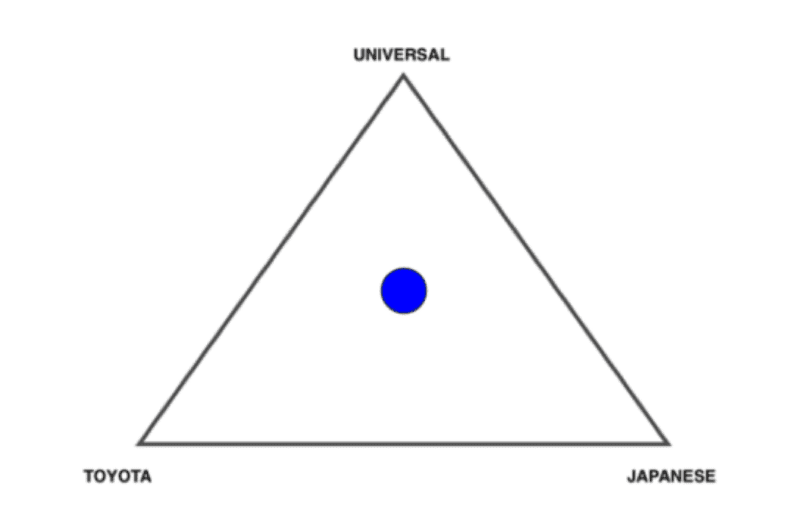

Katie challenged us with the John Shook questions at the beginning of the week. Is Lean a Japanese concept? Could it have been invented outside of Japan? We were asked to place a dot on Shook's triangle (see Figure 1). The three dimensions are as follows:

Are the Lean concepts unique to Toyota?

Are the Lean concepts unique to Japan?

Are the Lean concepts unique to Humans (universaL)?

The following triangle has a blue dot, which my opinion, was at the beginning of the week.

https://planet-lean.com/john-shook-toyota-interview-shinkansen/

The following triangle has a second blue dot of how I felt at the end of the week.

In the late '90s, when Americans started visiting Japanese companies, they would ask the Japanese employees what their Lean practices were like. The Japanese would look back with blank stares. What is this Lean thing? Lean and Kata are American descriptions of what Toyota did in the 1980s.

Lean consultants go into American companies and try to explain the concepts of Gemba, Seiri, Seiton, Seiso, Kaizen, Kanban, and Hoshin Kanri. It's like a telephone game in a different language. For example, a Lean dialog with an American company goes as follows:

Lean Consultant: You must use Kaizen.

American Worker: What's a Kaizen?

Lean Consultant: It's an event you must perform everyday.

We could ask the children questions at the elementary school, and someone asked one of them about their definition of Kaizen. The answer sounded different from the Lean consultant's answer above. In Japan, students already understand Kaizen as a way of life, so there is no need to translate it.